Condemnation to compensation: where are we post financial crisis?

Posted on: 27th June 2017 in

Finance

It is almost ten years to the month since a financial crisis stunned the global economy.

It’s perhaps ironic that it was news from Europe – not the United States – that led the first inklings of a profound and contagious issue. The freeze on two funds linked to packages of low-quality mortgages at France’s BNP Paribas followed a hasty meeting in Germany to help national lender IKE.

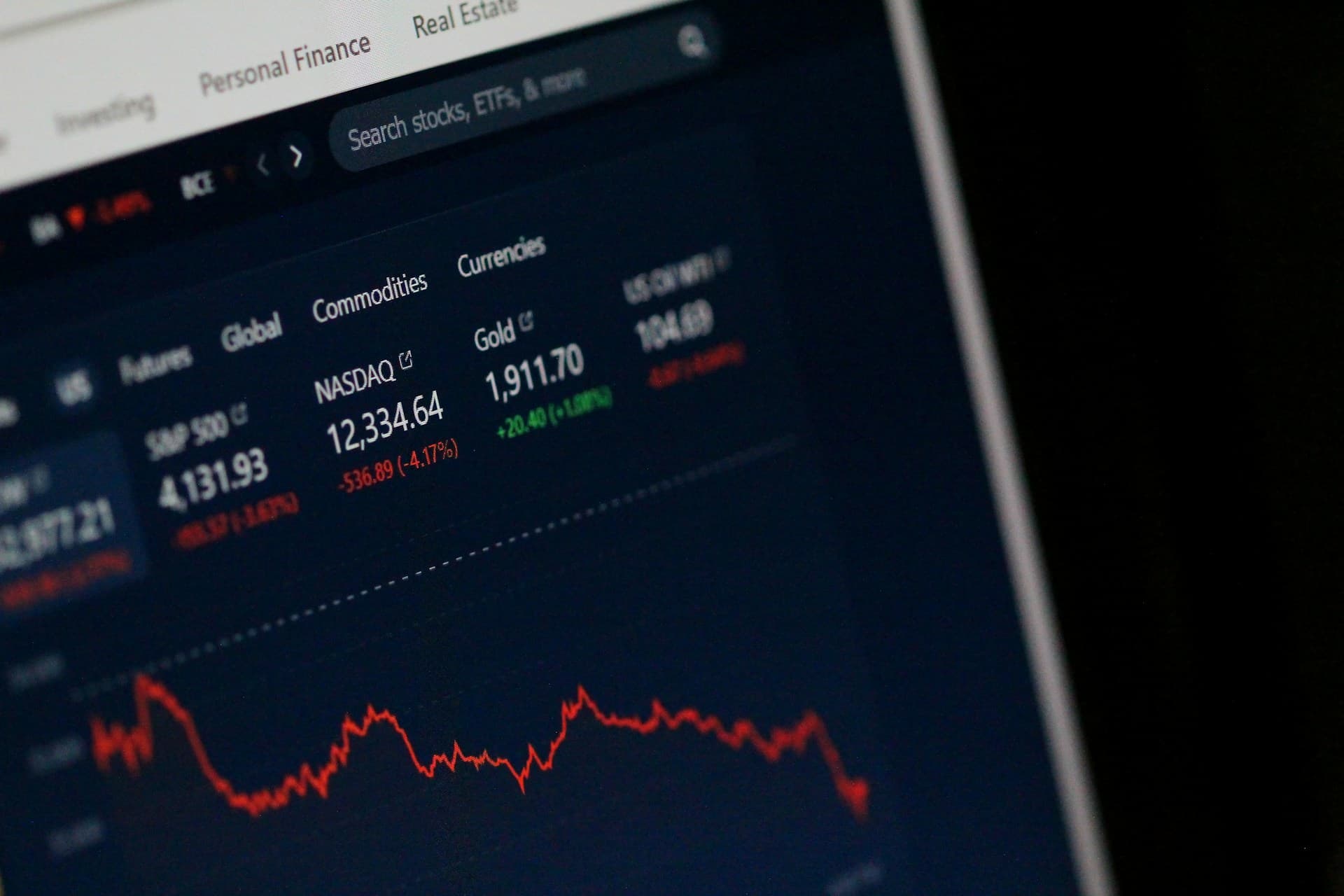

As the business-news became the news-news, mainstream media – and, by extension, the public – grappled with arcane terminology about tradable assets ‘backed’ by multiple books of house loans. The link between Mr Smith’s on-off mortgage payments in America’s midwest, the paralysing of mortgage lenders and international banks, stock market falls and global recession created a whirl of interconnectedness that still baffles today.

A few individuals came to prominence in the fallout. Hank Paulson became the hoarse voice of a US Treasury government tasked with steadying the big US lenders and cajoling Wall Street’s bank CEOs into getting their houses in order. Dick Fuld, then head of Lehman Brothers, turned from Wall Street bull to sacrificial lamb as his bank ceased operations globally.

Then, as US president-elect Barack Obama spoke on the side of the ‘Main Street’ of savers and retirees, there was Bernard Madoff. Though the New York investment firm with his name on the door had little to no contact with sub-prime products, global stock market falls finally uncovered a scam based on unerringly consistent investment performance, where existing investor ‘returns’ were in fact paid out of new investor inflows. While these investors were often intermediary institutions, it was their underlying retail savers who suddenly bore a very direct exposure.

The UK weathered its own consumer crises, including the ‘run’ on stricken UK lender Northern Rock, the part-nationalising of Lloyds TSB and RBS and the failure of Icelandic banks to the detriment of UK pension funds.

But whether complex products, the disruptions in wholesale lending, or the Madoff scandal, the common theme was the inconceivable yoke linking cavalier high finance with the man on the street.

As such, there seemed little doubt that consumer protection would be prominent as economies recovered. It is remarkable that a fund to compensate victims of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities was formed as late as 2013; more so that only in June 2017 did sources leak to media that it would start to pay-out before the end of this year. The years taken to process all the claims, on limited staff budgets, has been cited as the reason for such delays.

Other institutions have made hay for many years. The US’ Federal Trade Commission (FTC), a consumer protector that raises the bar for no-nonsense website content, has seen a number of significant wins over the big business in 2017 in particular. The FTC’s scope is not simply compensation for mismanaged savings, but the wider gamut of the consumer experience. In June this year, for example, it – along with the Department of Justice and the Attorneys General of four states – extracted a record $280 million from satellite TV provider Dish Network for its lax adherents to its own Do Not Call Registry. A reported 66 million calls were said to have been made to homeowners who had previously wished no further contact.

In the UK, a macro-review of regulation led to the splitting of the Financial Services Authority’s dual role as consumer protector and financial institution watchdog into two entities – the consumer-focused Financial Conduct Authority, and a Prudential Regulatory Authority – that focused on these areas, respectively.

As with the FTC, the growth of the Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS) has been a bright spot as the UK economy normalised. The FSCS pays out savers in the case of a failure in their deposit-holding institution. Though in existence since 2001, the crisis lifted the chance of consumer loss from a pre-2007 ‘hypothetical’ to ‘very real’ within two years.

In January this year, the FSCS pledged to increase the protected amount by GBP 10,000 to GBP 85,000 per consumer – GBP 170,000 for joint accounts. Good timing for the 2,550 savers with Plough & Share Credit Union, who will be compensated this month to those limits.

The Pension Protection Fund has also gained visibility. But rather than fully compensating members of company pension schemes in steep deficit, the PPF does no more than stopping the rot – taking on the liability of the scheme, ensuring some of the entitlements to the members but charging 10% off the top of the fund as running cost.

Backstop-schemes remind us that consumers and high finance will not be completely unconnected. Rather, they are a shield to clarify what risks are reasonably borne by the consumer as their deposits oil the wheels of global capital. Clarity of exposure, of expected returns and downside risk, and of the ultimate risk, the institution collapsing – providing defence when that risk line is overstepped.

The scalps claimed by the FTC and the UK’s authorities, and the successful payouts by the FSCS, inform us on the flip side that consumers can still fall victim at systemic and operational levels within products providers.

This is all the more significant as we plough further into the digital age. Nine years ago, the global crisis humbled a number of venerable institutions which now found themselves outside pin-striped food banks such as the Federal Reserve and the ECB. Such a fall required contrition and operational change to survive: it’s hard to keep up appearances on the high street and billboards otherwise. Today, the rise of online-only banks seems to have less of the same bricks-and-mortar presence. If they were to fail, would there be the same visibility as to its operations and senior management, the same pressure to amend what is wrong, or might they more easily dissolve into the ether without the strife of a centuries-old reputation to protect? Let us hope consumer protection doesn’t retreat or change with the terms of consumer-institution engagement.